Table of Contents

Gluten and food allergies silently fuel chronic inflammation. Learn how these triggers damage your gut and cause systemic inflammatory responses.

The bread, pasta and crackers many people consume daily may be quietly destroying their digestive tract. Gluten tears up the gut lining in susceptible individuals, creating microscopic holes that allow partially digested proteins to escape into the bloodstream. This leaky gut situation triggers immune responses that manifest as inflammation throughout the body. Identifying and eliminating these hidden triggers forms a critical step for anyone serious about learning to reduce inflammation naturally.

What gluten actually does to your gut

Gluten is a protein found in wheat, barley, rye and their derivatives. It gives bread its chewy texture and helps baked goods hold their shape. For thousands of years humans have consumed gluten-containing grains, though the modern versions differ substantially from ancient varieties.

When you eat gluten, your digestive system breaks it down into smaller peptide chains. In most people, these peptides get fully digested without incident. But in susceptible individuals, certain gluten peptides trigger a cascade of problems that extend far beyond the gut.

Gluten stimulates the release of zonulin, a protein that regulates the tight junctions between intestinal cells. These tight junctions normally keep the gut barrier sealed, allowing nutrients through while blocking larger particles. Zonulin loosens these junctions, increasing intestinal permeability.

Some zonulin release is normal and actually helps with nutrient absorption. The problem occurs when gluten consumption triggers excessive zonulin, loosening tight junctions beyond what’s healthy. The gut barrier becomes compromised, allowing substances through that should stay contained within the intestine.

This phenomenon, commonly called leaky gut, sets the stage for systemic inflammation. Partially digested food particles, bacteria and toxins that should remain in the gut instead enter circulation. Your immune system recognizes these substances as foreign invaders and mounts inflammatory responses against them.

The spectrum of gluten reactions

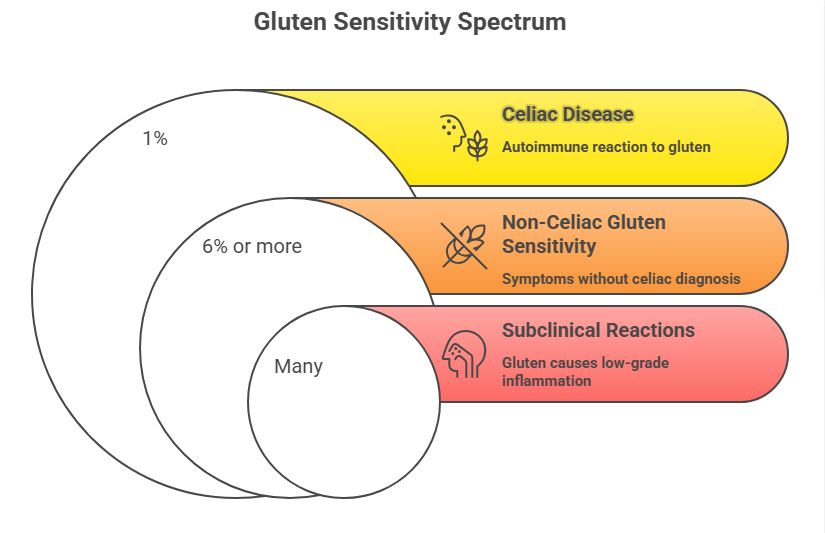

People respond to gluten along a spectrum from complete tolerance to severe autoimmune disease. Understanding where you fall on this spectrum helps determine whether gluten elimination might help your inflammatory symptoms.

Celiac disease

At the most severe end, celiac disease involves a full autoimmune reaction to gluten. The immune system attacks not just the gluten but also the intestinal lining itself. Villi, the finger-like projections that absorb nutrients, become flattened and damaged. Malabsorption and severe inflammation result.

Celiac affects roughly 1% of the population, though many cases remain undiagnosed. Blood tests and intestinal biopsy can confirm the diagnosis. People with celiac must avoid gluten completely and permanently. Even tiny amounts trigger immune reactions and intestinal damage.

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity

A larger group experiences problems with gluten without meeting criteria for celiac disease. These individuals test negative for celiac antibodies and don’t show the characteristic intestinal damage on biopsy. Yet they clearly feel worse when consuming gluten and better when avoiding it.

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity may affect 6% or more of the population. The exact mechanisms remain debated, but the clinical reality is clear. These people experience genuine symptoms from gluten that resolve with elimination. Dismissing their experience because they lack a celiac diagnosis misses the point.

Subclinical reactions

Even without obvious symptoms, gluten may cause low-grade inflammation in many people. The zonulin release and increased intestinal permeability occur to some degree in everyone who consumes gluten. Whether this causes problems depends on individual susceptibility and overall inflammatory load.

Someone with other inflammatory triggers might find that gluten tips them over their threshold even without being classically sensitive. Removing gluten reduces total inflammatory burden, allowing them to tolerate other factors better. This explains why gluten elimination helps some people who don’t fit neatly into sensitivity categories.

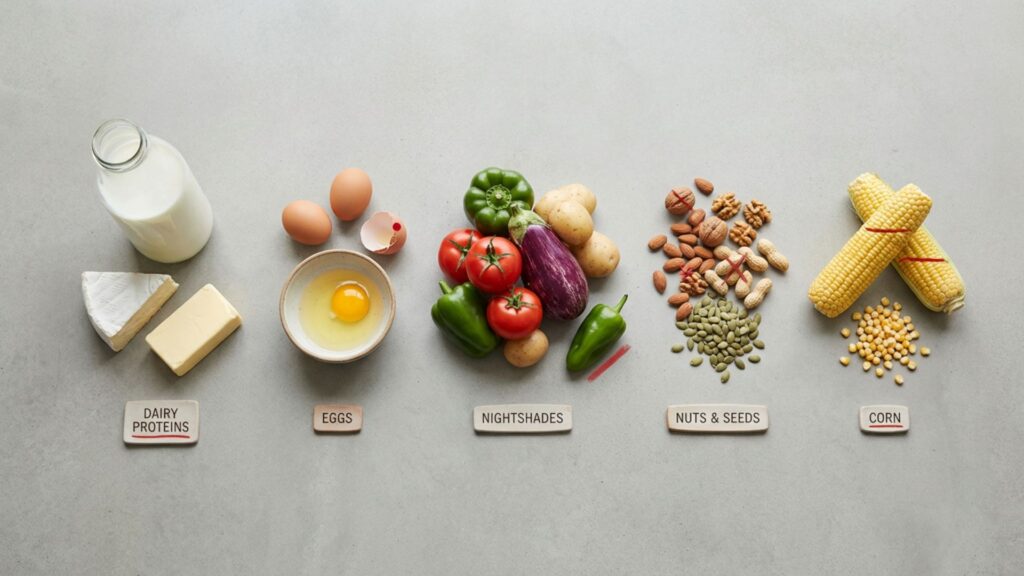

Beyond gluten: other food triggers

Gluten gets the most attention, but other foods commonly trigger inflammatory reactions. Identifying your personal triggers requires attention to how different foods affect you.

Dairy proteins

Casein and whey, the proteins in milk, cause problems for many people. Casein in particular has a molecular structure that can trigger immune reactions in susceptible individuals. Dairy allergy differs from lactose intolerance, which involves difficulty digesting milk sugar rather than immune reaction to proteins.

Symptoms of dairy sensitivity range from digestive upset to skin problems to joint pain. Some people tolerate certain dairy forms better than others. Aged cheeses and fermented dairy contain less intact casein than fresh milk. Butter and ghee have minimal protein and rarely cause reactions.

Eliminating dairy for three weeks then reintroducing it reveals whether it affects you. Many people discover that chronic congestion, skin issues or digestive problems clear up without dairy. Others find they tolerate it fine. Individual testing beats following general rules.

Eggs

Eggs rank among the top allergenic foods, particularly the whites. Egg allergy is most common in children and often resolves with age, but adults can develop or retain egg sensitivity. Both immediate allergic reactions and delayed sensitivity responses occur.

The proteins in egg whites, including ovalbumin and ovomucoid, trigger most reactions. Some egg-sensitive people tolerate yolks while reacting to whites. Others must avoid eggs entirely. Cooking alters egg proteins, so some people tolerate well-cooked eggs in baked goods while reacting to lightly cooked forms.

Nightshades

Tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, eggplant and related plants contain alkaloids that cause problems for some people. These compounds, particularly solanine and capsaicin, can increase intestinal permeability and trigger inflammation in susceptible individuals.

Joint pain and stiffness commonly accompany nightshade sensitivity. People with arthritis sometimes improve dramatically when eliminating this food family. The connection isn’t universal, but it’s common enough to warrant a trial elimination for anyone with inflammatory joint problems.

Nuts and seeds

Tree nuts and peanuts cause classic allergic reactions in many people. Beyond immediate allergies, some individuals experience delayed inflammatory responses to nuts and seeds. The omega-6 fatty acids and phytic acid in these foods contribute to inflammation in sensitive people.

Nut sensitivities often cause skin reactions, digestive upset or increased mucus production. People who snack heavily on nuts while trying to eat healthy sometimes find they do better without them. As with other foods, individual response varies widely.

Corn

Corn allergy is less common than other grain reactions but does occur. More frequently, people react to the highly processed corn derivatives ubiquitous in packaged foods. Corn syrup, corn starch, maltodextrin and other corn-derived ingredients appear on countless ingredient lists.

Eliminating corn proves challenging given its prevalence in processed foods. Eating whole, unprocessed foods automatically eliminates most corn exposure. Those with true corn sensitivity must read labels carefully and avoid restaurants that may use corn-based ingredients.

| Food | Common Symptoms | Prevalence |

| Gluten | Digestive issues, fatigue, brain fog, joint pain | 6-7% sensitivity |

| Dairy | Congestion, skin problems, digestive upset | Very common |

| Eggs | Skin reactions, digestive issues | Common, especially in children |

| Nightshades | Joint pain, digestive inflammation | Variable |

| Nuts | Skin reactions, digestive issues, inflammation | Common |

| Corn | Various, often subtle | Less common |

How food sensitivities develop

Understanding why food sensitivities develop helps prevent new ones from forming and potentially allows recovery from existing ones. The gut plays a central role in this process.

Leaky gut as the starting point

Most food sensitivities trace back to compromised intestinal permeability. When the gut barrier fails, large food particles enter circulation before being fully digested. Your immune system encounters these particles and may develop antibodies against them.

Once antibodies form, every subsequent exposure to that food triggers an immune response. This explains why people often become sensitive to foods they eat frequently. Regular exposure while the gut is leaky provides repeated opportunities for sensitization.

Healing the gut barrier often allows food tolerances to recover. Foods that previously caused reactions may become tolerable again once intestinal permeability normalizes. This doesn’t happen immediately and requires dedicated gut healing alongside food elimination.

The role of gut dysbiosis

Imbalanced gut bacteria contribute to both intestinal permeability and food reactions. Certain bacterial species promote gut barrier integrity while others produce compounds that damage it. Dysbiosis tips the balance toward barrier breakdown.

Pathogenic bacteria and yeast also produce toxins that directly trigger inflammation. Candida overgrowth commonly accompanies food sensitivities. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth creates its own inflammatory problems. Addressing gut microbial balance supports recovery from food sensitivities.

Restoring healthy gut flora through diet, probiotics and sometimes antimicrobial herbs helps heal the underlying dysfunction. As the microbiome improves, food tolerances often expand. People sometimes regain ability to eat foods they’d eliminated for years.

Immune dysregulation

A healthy immune system maintains oral tolerance, the ability to recognize food proteins as harmless. Chronic inflammation, stress and nutritional deficiencies can impair this tolerance, making new sensitizations more likely.

Vitamin D plays an important role in oral tolerance. Deficiency increases risk of developing food allergies and sensitivities. Optimizing vitamin D supports healthy immune regulation that distinguishes friend from foe appropriately.

Chronic stress impairs immune function through cortisol effects on immune cells. People under high stress often develop new food sensitivities or see existing ones worsen. Addressing stress alongside dietary factors improves outcomes.

Identifying your personal triggers

Figuring out which foods trigger your inflammation requires systematic testing. Random elimination and haphazard reintroduction provide unreliable information. A structured approach yields clearer answers.

Elimination diet protocol

The gold standard for identifying food sensitivities involves eliminating suspected foods completely for a defined period, then reintroducing them one at a time while monitoring for reactions.

Start by removing the most common triggers: gluten, dairy, eggs, corn, soy, nuts and nightshades. Maintain strict elimination for at least three weeks. This allows time for existing inflammation to calm and antibodies to clear. Some people need four to six weeks for complete settling.

During elimination, eat simply from foods you’re confident don’t cause problems. Quality meats, fish, most vegetables, fruits and healthy fats provide adequate nutrition while testing. Keep a food diary noting what you eat and any symptoms, even subtle ones.

After the elimination period, reintroduce foods one at a time with three days between each new food. Eat a meaningful amount of the test food, not just a tiny taste. Monitor for 72 hours since reactions can be delayed. Note any symptoms including digestive changes, energy shifts, skin changes, joint pain, headaches or mood effects.

Interpreting reactions

Clear reactions make decisions easy. If reintroducing gluten causes obvious bloating, fatigue and joint pain, you have your answer. These dramatic responses provide certainty about which foods to avoid.

Subtle reactions require more attention. A vague sense of not feeling quite right, slightly disrupted sleep or minor skin changes might indicate sensitivity. Repeat the test to confirm before deciding. True sensitivities reproduce consistently.

Some reactions delay significantly. Gluten can cause symptoms 24 to 72 hours after consumption. Keep this timeframe in mind when evaluating reactions. If you eat gluten on Monday and feel terrible on Wednesday, the connection exists even though the timing seems off.

Testing options

Blood tests measuring food-specific antibodies exist but have significant limitations. IgG antibody tests, widely marketed for food sensitivity identification, measure exposure rather than true allergy. Elevated antibodies may simply indicate you eat that food regularly.

IgE testing identifies classic allergies but misses sensitivities that work through different mechanisms. A negative IgE test doesn’t rule out food reactions. These tests have their place but don’t replace elimination diet testing.

Some practitioners use other testing methods including muscle testing, electrodermal screening and various proprietary panels. Evidence supporting these methods remains weak. Elimination and reintroduction testing, while time-consuming, provides the most reliable information about your individual responses.

Living with food sensitivities

Once you’ve identified your triggers, practical management becomes the focus. Complete avoidance of reactive foods allows inflammation to resolve while partial avoidance often maintains problems.

Reading labels obsessively

Food manufacturers hide problem ingredients under various names. Gluten appears as wheat, barley, rye, malt, brewer’s yeast and sometimes hidden in flavorings or sauces. Dairy shows up as casein, whey, lactose and in seemingly non-dairy foods like some breads.

Learning the alternative names for your triggers protects you from inadvertent exposure. Keep a list on your phone for reference when shopping. Over time, recognizing safe versus problematic products becomes automatic.

The phrases may contain and processed in a facility that processes indicate cross-contamination risk. How strictly you need to avoid these depends on your sensitivity level. People with celiac disease or severe allergies must avoid any contamination. Those with milder sensitivities may tolerate trace amounts.

Restaurant strategies

Eating out with food sensitivities requires advance planning. Many restaurants now accommodate dietary restrictions, but kitchen practices vary widely. Cross-contamination happens easily when cooks aren’t careful.

Calling ahead to discuss your needs works better than explaining at the table. Speak with a manager rather than just a server. Ask specific questions about preparation methods and shared cooking surfaces. The more severe your reactions, the more cautious you must be.

Some cuisines naturally accommodate certain restrictions better than others. Mexican food works well for gluten-free eating. Thai and Vietnamese restaurants often accommodate multiple restrictions. Italian restaurants present challenges for gluten avoidance given their reliance on pasta and bread.

Social situations

Food sensitivities complicate social eating. Holiday gatherings, dinner parties and work events often center on foods you can’t eat. Managing these situations without becoming isolated requires creativity and communication.

Eating before events ensures you won’t go hungry regardless of what’s available. Bringing a dish you can eat guarantees at least one safe option. Focusing on socializing rather than food shifts the emphasis away from what you’re not eating.

Close friends and family usually accommodate restrictions once they understand. Brief explanations without excessive detail work best. Most people want to help once they know what you need. Those who don’t accommodate after clear communication may need boundaries regardless of food issues.

The morphine-like effects of gluten

Here’s something that surprises many people: gluten breaks down into compounds called gluteomorphins that bind to opioid receptors in your brain. These morphine-like peptides create mild euphoria and pain reduction that can mask the very damage gluten causes.

This explains why eliminating gluten sometimes feels harder than it should. The withdrawal from these opioid compounds creates cravings and discomfort similar to quitting other addictive substances. The first week or two without gluten can feel genuinely difficult even when intellectually committed to elimination.

The masking effect also explains why some people don’t connect gluten to their symptoms. The gluteomorphins numb the pain and discomfort from intestinal damage. You might feel fine eating gluten while your gut suffers invisible injury. Only after eliminating gluten and clearing these compounds do you notice how much better you feel and how bad you actually felt before.

Dairy contains similar opioid peptides called casomorphins. The combination of gluten and dairy provides a double dose of these compounds. People eliminating both often experience more significant withdrawal than those eliminating either alone.

Healing after elimination

Removing trigger foods stops ongoing damage but doesn’t automatically repair existing harm. Active gut healing accelerates recovery and may eventually allow reintroduction of some eliminated foods.

Gut healing nutrients

L-glutamine provides direct fuel for intestinal cells and supports barrier repair. Typical therapeutic doses range from 5 to 20 grams daily. Taking glutamine on an empty stomach maximizes intestinal uptake.

Zinc supports gut barrier integrity and immune function. Zinc carnosine specifically adheres to damaged intestinal lining, delivering zinc directly where healing is needed. This form works particularly well for gut repair.

Collagen and bone broth provide amino acids that support connective tissue repair throughout the gut. The gelatin in bone broth soothes inflamed tissue while delivering building blocks for regeneration.

Timeline expectations

Gut healing takes time, typically months rather than weeks. Strict elimination combined with active healing support produces faster results. Partial compliance or continued exposure to triggers prolongs the process indefinitely.

Most people notice symptom improvements within two to four weeks of strict elimination. Deeper healing continues for three to six months or longer. Some damage from years of exposure takes considerable time to fully repair.

Patience serves you during this process. The temptation to reintroduce foods too early often leads to setbacks. Allow adequate healing time before testing foods you’ve eliminated. Your future tolerance depends on how thoroughly you heal now.

Moving forward

Food sensitivities represent one piece of the inflammation puzzle. Identifying and eliminating your triggers removes a significant inflammatory burden, but other factors may also need attention.

Supplements can accelerate healing and address deficiencies that developed from malabsorption. Many people with food sensitivities have depleted nutrient stores from years of poor absorption. Strategic supplementation supports recovery while diet provides the foundation. Learning about the best natural supplements for inflammation helps you choose interventions that complement your elimination diet and gut healing protocol.